If you've ever so much as peeked behind the curtain of Web user interfaces before, you'll know what the class property is for. It's for connecting HTML to CSS, right? I'm here to tell you it's time for us to stop using it. Class names are an archaic system that serves as a poor proxy for your UI primitives, and worse they're co-opted in awkward ways which results in combinatorial explosion of weird edge cases. Let's get into it, first with a boring history lesson which you've all heard a million times before:

Class is old. Like real old

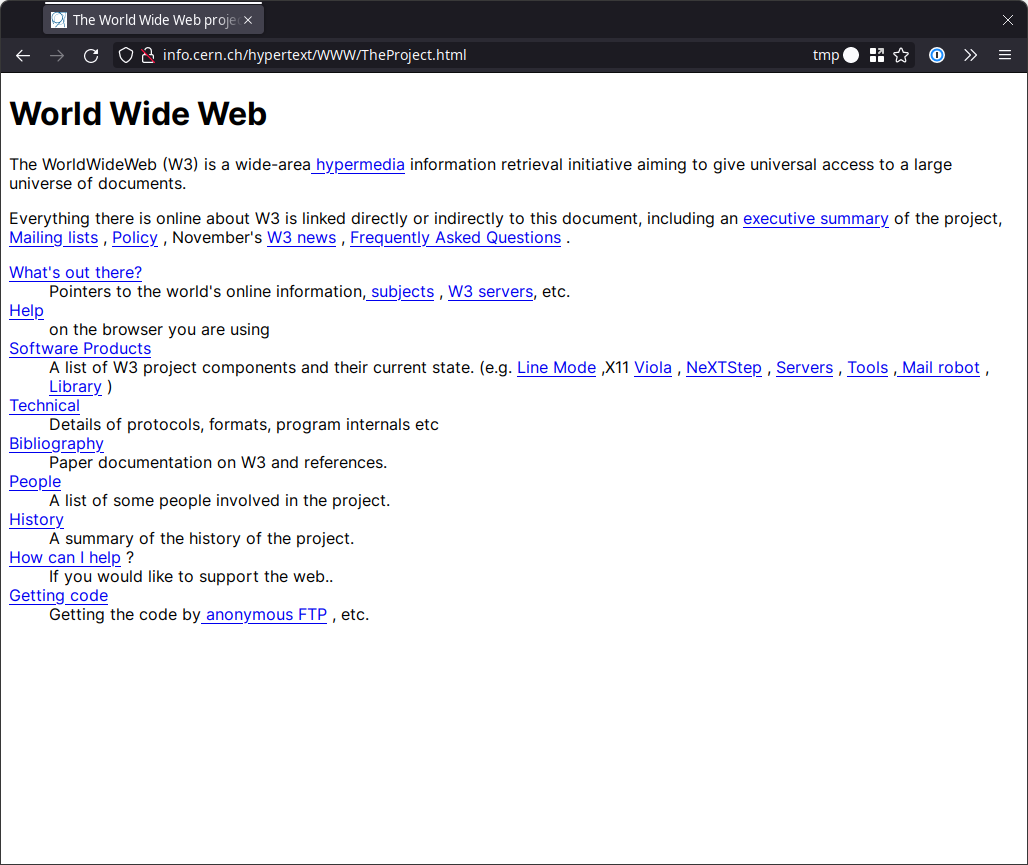

HTML 2.0 (1996) was the first published specification of HTML, and it had a fixed list of tag names, and each tag had a fixed list of allowed attributes. HTML 2.0 documents could not be styled - what was the point? Computers were black and white then, kiddos! The closest thing to customising the style of an HTML 2.0 tag was the <pre> tag which had a width attribute. HTML 3.0 spent a few years being worked on, meanwhile Netscape and Microsoft were adding all sorts of weird extensions such as the beloved <marquee> and <blink> tags. Eventually everyone settled their differences, and HTML 3.2 was born in 1997, which allowed the <body> tag to be "styled" with attributes like bgcolor and text.

Meanwhile, CSS was being invented as a way to supply some layout and styling to web pages to make them a bit less bland. HTML 3.2 had a short lived history, because that same year, 1997, HTML 4.0 was published, which included mechanisms to support CSS - including the new "Element Identifiers"; the id and class attributes:

To increase the granularity of control over elements, a new attribute has been added to HTML [2]: 'CLASS'. All elements inside the 'BODY' element can be classed, and the class can be addressed in the style sheet CSS Level 1

These attributes allowed us, with a limited set of tags, to define "classes" of elements which we could style. For example a <div class="panel"> might look considerably different to a <div class="card"> even though they share the same tag name. Conceptually you could think of these as classical inheritance (so class Card extends Div) - inherit the semantics and base styles of div while making a re-usable style for a Card class.

Since 1997, we've had more than 20 years of innovation of the Web. There are myriad new ways to structure your CSS.

"Class is old" is not an argument against classes (the only argument against using something that's old is toward food). However it illustrates that they solved a problem within a period of constraint. The web was young, browsers we less complex, and digital design was less mature. We didn't need a more complex solution at the time.

Scaling Class selectors.

If we continue to think of the class property as an analog to OOP Classes - it's rare that you'd have a class that takes no parameters or has no state. The intrinsic value of capital

C Classes is that they have "modes" through parameters, and can change their state through methods. CSS has pseudo selectors which represent limited portions of state such as :hover but for representing custom state or modality within a class, you need to use yet-more classes. The problem is class just takes a list of strings...

Take our Card example. If we wanted to parameterise Card to take a size option which is either Big Medium or Small, a rounded boolean, and an align option which is either Left, Right, or Center. Let's say our Card also can be lazily loaded, so we want to represent a state of Loading and Loaded. We have several options at our disposal, but each with limitations:

- We can present them as additional classes, for example

<div class="Card big">. One problem with this approach is that it lack namespaces; some other CSS can come along and co-opt whatbigmeans for their own component which can conflict. A way around this is to combine selectors in your CSS:.Card.big {}but this can cause specificity issues, which can create problems further down the line. - We can present them as distinct "concrete" classes, for example

<div class="BigCard">. One issue with this approach is that we potentially produce a lot of duplicate CSS, asBigCardandSmallCardwill likely have some shared CSS. This approach also has scalability issues, hitting the combinatorial explosion problem; with just thesizeoption we need to create 3 classes, but addroundedand that becomes six, now addalignand we have 18 classes to create. - We can namespace the classes parameters, for example

<div class="Card Card--big">. This helps alleviate conflicts, and avoids the combinatorial explosion issue, but it can be overly wordy with a lot of duplicate typing, and it suffers another issue around misuse: what happens when I use theCard--bigclass withoutCard?

Modern CSS can solve some of these issues, for example :is() and :where() pseudo class functions can massage the specificity of a selector ( .Card:is(.big) has an equal specificity to .Card). We could also use languages like SASS to help on authoring these systems, thanks to nesting and mixins which can alleviate the pain of duplication. These improve developer experience but fail to address the root problems.

We also have several problems which classes inherently cannot solve:

- With transitory state classes like

loadingandloaded, it is possible for code to arbitrarily apply these classes to the element, even when the element is not actually loading. The way to counter this is with engineering discipline (hard to scale to many engineers) or tooling (hard to maintain). - With mutually exclusive classes like

BigandSmall, it is possible for elements to apply both classes at once, and none of the class naming systems can correct for this, unless you specifically counter it with, again, more tooling or more code (for example.Card.big.small { border: 10px solid red }).

We also have a cottage industry of CSS pseudo-specifications that try to solve these issues, but they're not really the solution:

BEM is not the solution

BEM or "Block Element Modifier" proposes a reasonably robust and scalable solution for parametrising classes. It uses namespaces which prevents re-use issues, at the expense of verbosity. It has hard rules around naming, which makes the code a little easier to reason about.

.Card { }

.Card--size-big { width: 100%; }

.Card--size-small { width: 25%; }

.Card--rounded { border-radius: 6px }

.Card--align-left { text-align: left }

.Card--align-right { text-align: right }

.Card--align-center { text-align: center }

.Card__Title { /* Sub components! */ }BEM gives you a small amount of consistency but doesn't solve the two problems core to classes (control for invariance). I can apply class="Card--size-big Card--size-small" to a single element, and the framework BEM provides cannot stop me. Likewise, there's no notion of protected properties in BEM, so I have to trust that you won't add .Card--is-loading to an element. These problems are easier to spot, thanks to the naming framework, but they're as good as prefixing JavaScript methods with _. It works if you follow the rules, but there's no enforcement if you don't.

Another big issue with BEM is that representing dynamic state through JS is an absolutely grueling amount of boilerplate:

/* This is the smallest I can think to make this without adding helper functions */

function changeCardSize(card, newSize: 'big' | 'small' | 'medium') {

card.classList.toggle('.Card--size-big', newSize === 'big')

card.classList.toggle('.Card--size-medium', newSize === 'medium')

card.classList.toggle('.Card--size-small', newSize === 'small')

}Solutions around the boilerplate include using helper functions, but this is again merely pushing the problem down, rather than solving it.

Atomic CSS is not the solution

Atomic CSS or "utility classes" does away with the OOP concept of representing your design system components like "Card" and instead opts for classes to be used as an abstraction from CSS properties. It plays well into most design systems which are strictly a subset of CSS itself (CSS allows near limitless colours for example, while your brand palette probably allows for less than 100 colours). The popular "Tailwind" library is perhaps the most notable implementation of atomic CSS, but if you're unfamiliar it might look a bit like this:

.w-big { width: 100% }

.w-small { width: 25% }

.h-big { height: 100% }

.al-l { text-align: left }

.al-r { text-align: right }

.br-r { border-radius: 6px }

/* and so on... */Atomic CSS, again, doesn't solve the two major concerns with classes. I can still apply class="w-big w-small" to my element, and there's still no way to utilise protected classes.

Atomic CSS also usually results in chaos within your markup. To cut down on verbosity this system usually prefers short class names that are a handful of characters such as br instead of border-radius. To represent our Card example in this system requires a smörgåsbord of inscrutable class names, and this is a trivial example:

<!-- A Big Card -->

<div class="w-big h-big al-l br-r"></div>Atomic CSS also leaves a lot of the benefits of CSS on the cutting room floor. Atomic CSS reduces everyone to using the documentation; experienced designers who may have a lot of experience writing CSS now need to confer to a lookup table ("I want flex-shrink: 0, is that flex-shrink-0 or shrink-0?"). All utilities are generally one class name, which means we lose any benefits from specificity; worse if we introduce specifity through mixing methodologies or using media queries or inline styles the whole thing falls apart. The typical response to specificity issues it to counter it with more specificity; GitHub's Primer CSS works around this by adding !important to every utility class, which then creates new problems.

While on the topic of media queries, we find the biggest problem with Atomic CSS which is that it leaves responsive design open to interpretation. Many implementations resort to providing classes that are only applied during a responsive breakpoint, which only serves to further litter the markup, and suffers from the combinatorial explosion issue. Here's a snippet of just 2 of the widths across 2 breakpoints as defined in tailwind CSS:

.w-96 { width: 24rem }

.w-80 { width: 20rem }

@media (min-width: 640px) {

.sm\:w-96 { width: 24rem; }

.sm\:w-80 { width: 20rem; }

}

@media (min-width: 768px) {

.md\:w-96 { width: 24rem; }

.md\:w-80 { width: 20rem; }

}<!-- A Big Card on Big Screens, a Small Card on Small Screens -->

<div class="w-96 sm:w-80 al-l br-r"></div>At first blush a utility class system might seem like a boon to a design system, but when applied to the markup we quickly see the problems: being unable to represent components easily in markup leads to a design system looking for other solutions such as providing markup with attached class names to represent a component - which usually results in the design system implementing components across a multitude of frameworks.

There are a plethora of other issues with the Utility CSS methodology, and with it a plethora of articles. If you consider this a suitable solution, I'd encourage you to invest time researching the pitfalls, but I don't want to spend too long on this.

CSS Modules is not the solution

CSS Modules really only solves one problem: the "selector collision" issue. You can author CSS in a single file, which then becomes the class namespace, and run it through a tool which which prepends the namespace and tacks random characters at the end. The random characters are generated during build, as a way to prevent custom written styles that don't use CSS modules colliding with those that do. This means our card css...

.card { /* The "baseline" component */ }

.big { width: 100% }

.small { width: 25% }

/* ... and so on ... */...gets transformed during a build step to become...

.card_166056 { /* ... */ }

.card_big_166056 { width: 100% }

.card_small_166056 { width: 25% }

/* ... and so on ... */This seems like it solves the issues around BEM, as you don't have to write the namespaces everywhere! But instead it trades it for tooling that needs to be developed and maintained across all of your stack that presents UI; this requires your templating framework, JS runtime (if that's different) and your CSS compiler to all understand and use the same CSS Module system which creating a multitude of dependencies across your codebase. If you have a large organisation with multiple websites to maintain, perhaps written in multiple languages, you have to develop and maintain tooling across all of them. Now your design system team is tasked (or burdens other engineering teams) with orchestrating all of this tooling.

But we're still stuck with the two core problems also! At the risk of repeating myself, class="big small" is still left unsolved. I can sort-of get protected classes if I add more tooling to my codebase to ensure that only 1 component uses 1 CSS Module file, but it's a solution that has all the pitfalls of the larger technology: just a ton more tooling.

CSS Modules also completely destroy any chance of caching your CSS beyond a single deploy. The only way to cache CSS like this is to make the class name transform deterministic, which defeats the purpose of using the hash in the first place as - without engineering discipline (hard to scale) a developer can hard-code the hashed class names in their HTML.

The problem all of these solutions have

The key issue with all of these solutions is that they centre around the class property as the only way to represent the state of an object. Classes, being a list of arbitrary strings, have no key-values, no private state, no complex types (which also means IDE support is quite limited) and rely on custom DSLs like BEM just to make them slightly more usable. We keep trying to implement parameters into a Set<string> when what we want is a Map<string, T>.

The solution to all of these problems

I humbly put forward that modern web development provides us all the utilities to move away from class names and implement something much more robust, with some fairly straightforward changes:

Attributes

Attributes allow us to parameterise a component using a key-value representation, very similar to Map<string, T>. Browsers come with a wealth of selector functions to parse the values of an attribute. Given our card example, the full CSS can be expressed simply as:

.Card { /* ... */ }

.Card[data-size=big] { width: 100%; }

.Card[data-size=medium] { width: 50%; }

.Card[data-size=small] { width: 25%; }

.Card[data-align=left] { text-align: left; }

.Card[data-align=right] { text-align: right; }

.Card[data-align=center] { text-align: center; }HTML attributes can only be expressed once, meaning <div data-size="big" data-size="small"> will only match data-size=big. This solves the problem of invariants, where the other solutions do not.

It might look similar to BEM, and has a lot of the same benefits. When authoring CSS it's certainly similar, but it demonstrates its advantage when we come to authoring the HTML, which is that it is much easier to distinguish each of the states discretely:

<div class="Card" data-size="big" data-align="center"></div>It's also far more straightforward to make values dynamic with JS:

function changeCardSize(card, newSize: 'big' | 'small' | 'medium') {

card.setAttribute('data-size', newSize)

}The data- prefix can be a little unwieldy but it allows for the widest compatibility with tools and frameworks. Using attributes without some kind of namespace can be a little dangerous, as you risk clobbering HTML's global attributes. As long as your attribute name has a dash it should be quite safe; for example you might invent your own namespace for addressing CSS parameters, which gives the benefit of readability:

.Card[my-align=left] { text-align: left; }This also has other tangible benefits. Attribute selectors like [attr~"val"] allow you to treat the value as if it were a list. This can be useful when you want flexibility in styling parts of a component, such as applying a style to one or more border sides:

.Card { border: 10px solid var(--brand-color) }

.Card[data-border-collapse~="top"] { border-top: 0 }

.Card[data-border-collapse~="right"] { border-right: 0 }

.Card[data-border-collapse~="bottom"] { border-bottom: 0 }

.Card[data-border-collapse~="left"] { border-left: 0 }<div class="card" data-border-collapse="left right"></div>The up and coming CSS Values 5 specification also allows for attributes to penetrate into CSS properties, much like CSS variables. It's common for design systems to have various size levels abstracting away pixel values (for example pad-size might go from 1-6 where each number represents range from 3px to 18px):

<div class="card" pad-size="2"></div>.Card {

/* Take the `pad-size` attribute, and coerce it to a `px` value. */

/* If it's not present, fall back to 1px */

--padding-size: attr(pad-size px, 1px)

/* Make the padding size a multiple of 3px */

--padding-px: calc(var(--padding-size) * 3px);

padding: var(--padding-px);

}

Of course with enough typing this could be solved today at least for bounded values (which most design systems express):

.Card {

--padding-size: 1;

--padding-px: calc(var(--padding-size) * 3px)

padding: var(--padding-px);

}

.Card[pad-size=2] { --padding-size: 2 }

.Card[pad-size=3] { --padding-size: 3 }

.Card[pad-size=4] { --padding-size: 4 }

.Card[pad-size=5] { --padding-size: 5 }

.Card[pad-size=6] { --padding-size: 6 }Admittedly this is an uncomfortable amount of boilerplate, but it's a workaround for now.

Custom Tag Names

If you got down to here you're probably screaming at your monitor saying "Keith you absolute buffoon, you're still using class names! .Card is a class!". Well that's the easy bit. HTML5 allows for custom tags, any tag that isn't recognised by the parser is an unknown element that can be freely styled as you see fit. Unknown tags come with no default user-agent styling: by default it behaves like a <span>. This is useful because we can express a component by using the literal tag name instead of class:

<my-card data-size="big"></my-card>my-card { /* ... */ }

my-card[data-size="big"] { width: 100% }These elements are completely valid HTML5 syntax and do not need any additional definitions, no special DTD or meta tag, no JavaScript. Just like attributes it's a good idea to include a - which the spec accommodates for and won't clobber. Using a - also means you can opt into even more powerful tools like Custom Element Definitions which can allow for JavaScript interactivity. With Custom Elements you can use custom CSS states, which takes us to the next level of capability:

Custom State (custom pseudo selectors)

If your components have any level of interactivity, they might want to change style due to some state change. You might be familiar with input[type=checkbox] elements having a :checked pseudo class, which allows CSS to hook into their internal state. With our Card example, we wanted to introduce a loading state, so we can decorate it in CSS; replete with animated spinners, while a fully loaded card might want to represent itself with a green border. With a little JavaScript, you can define your tag as a Custom Elements, grab the internal state object and manipulate it to represent these as custom pseudo selectors for your custom tag:

customElements.define('my-card', class extends HTMLElement {

#internal = this.attachInternals()

async connectedCallback() {

this.#internal.states.add('loading')

await fetchData()

this.#internal.states.delete('loading')

this.#internal.states.add('loaded')

}

})my-card:state(loading) { background: url(./spinner.svg) }

my-card:state(loaded) { border: 2px solid green }Custom states can be really powerful because they allow an element to represent itself in a modality under certain conditions without altering its markup, which means the element can retain full control of its states, and they cannot be controlled from the outside (unless the element allows it). You might go so far as to call it... internal state. They're supported in all modern browsers and for the old or esoteric ones a polyfill is available (although it has some caveats).

Conclusion

There are many great ways we express states and parameters of a component without having to shoehorn them into an archaic system like the class attribute. We have mechanisms today to replace it, we just need to unleash ourselves from our own shackles. Upcoming standards will allow us to express ideas in powerful new ways.

Still attached to utility classes? Think Custom Elements are the work of Satan? I'd love to hear your thoughts on this. Social links in the header.